Understanding the Unbanked, and Why Postal Banking Won’t Help Them

The unbanked are more than just a dataset.

Ahead of today’s Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions hearing on Banking the Unbanked, I thought it might be helpful to explain why it’s critically important that we seek to understand why millions of people in this country are unbanked before “solutions” are prescribed.

For example, a new study from a team of authors at the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions Initiative found that post offices may be just the solution for America’s unbanked. There’s only one problem: the authors were operating under a false premise. In arguing that “postal banking could provide a lifeline to the millions of Americans without a bank account,” the team appears to have overlooked the very reasons said Americans are unbanked.

Authors Terri Friedline, Xanthippe Wedel, Natalie Peterson, and Ameya Pawar base their argument on the idea of banking deserts, or areas without a brick-and-mortar bank or credit union. The authors find that U.S. census tracts with a post office often lack community banks and credit unions: 69% do not have a community bank, 75% do not have a credit union, and 24% have neither.1 Therefore, they conclude that if post offices act as banks, it would bring the unbanked into the banking system.

A Solution in Search of a Problem

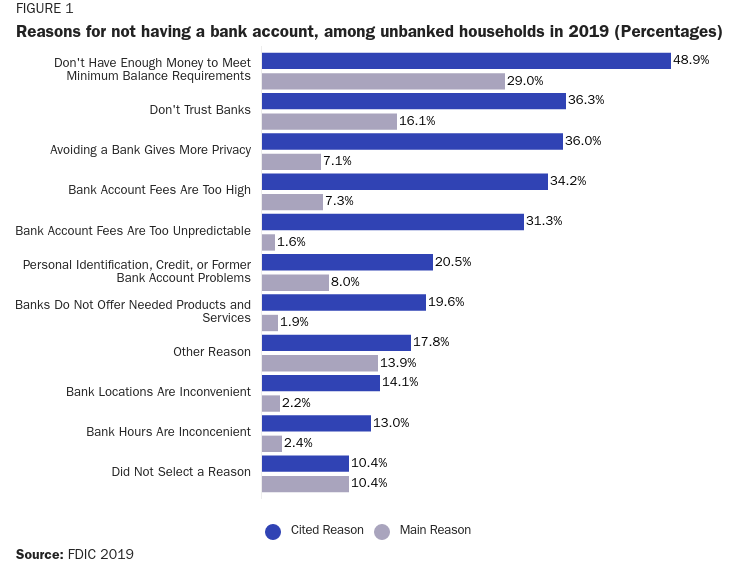

Unfortunately, postal banking is a solution in search of a problem when it comes to access to physical locations. The FDIC’s 2019 survey on the household use of banking and financial services confirmed that much. In addition to showing that 75% of the unbanked are not interested in having a bank account, the survey shows their reasons for being unbanked. Out of the ten options listed, inconvenient bank locations were ranked nearly last (See Figure 1).

Worse yet, even if postal banking would eliminate the issue of inconvenient locations, it does little to eliminate the unbanked population’s other concerns. The unbanked avoid the banking system due to everything from the difficulty of meeting minimum balance requirements to concerns about trust and privacy. A postal banking system may be able to lower the costs of banking through taxpayer subsidies, but it is not clear how it would win the public’s trust—especially with the public’s trust for the U.S. government at historic lows.

People, Not Numbers

When speaking in statistics, it is easy to forget that what we call the “unbanked” is a group made up of millions of people, each with different wants, lifestyles, and pasts. If there is a solution—or, what is most likely a set of solutions—that can help the unbanked, it must take into account that they are real people, not a dataset. And while it’s difficult to address every factor at work, any solution should, at the very least, address all of the data we do have.

Notably, only 30% of census tracts have a post office and the authors do not consider larger financial institutions.